Science education refers to the process of equipping students with fundamental scientific skills, fostering curiosity and positive attitudes towards science, and enabling them to understand the natural world, make informed personal decisions, and engage with the scientific and technological aspects of society. It emphasizes inquiry-based learning and the development of scientific thinking rather than mere acquisition of scientific knowledge.

AI generated definition based on: International Encyclopedia of Education (Third Edition), 2010

Evaluation of Science Education Programs

At present, science education is one of the primary requirements of a literate society where students should be strengthened with basic scientific skills. They should develop curiosity and excitement as well as positive attitudes toward science in order to understand the natural world around them, use scientific processes in dealing with their personal decisions, cope with the scientific and technological aspects of today’s world, and, eventually, act as scientifically literate persons to contribute to productivity in society (Buxto and Provenzo, 2007; Carin and Bass, 2001; Gregory and Hammerman, 2008). Therefore, a science program should stimulate the engagement in science by emphasizing the processes in the making of science, organizing scientific ideas, and developing a scientific temper through inquiry rather than imparing mere scientific knowledge (Bloom, 2006; Freeman and Taylor, 2006). Within this context, evaluation becomes a process dealing with all the possible indicators of a successful implementation through a systematic procedure which consists of a formal appraisal of the quality of educational phenomena (Popham, 1993). This is the program-accountability issue (Scheerens et al., 2007). Thus, program accountability is established through appraising the quality in line with the program’s overall planned conceptual framework in terms of its scope and good choice of objectives, its implementation practices in line with planned activities, and the level of attainments of the objectives (Scheerens et al., 2007). For program accountability, it is also important to consider the satisfaction of various stakeholders, education policymakers, experts, and any other agency dealing with the program outcomes, since every program should serve the intellectual and social development of a society (Marsh and Willis, 2007). Thus, evaluating a science program is a dynamic process in which any information about the quality will provide continuous feedback to its conceptual framework as well as the implementation practices.

Steps for evaluating a science program

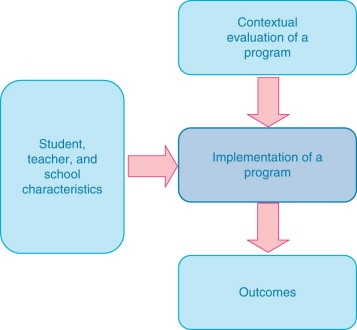

In general, a program evaluation attempt needs to address the quality issue – in terms of input, process, and output (Posner, 1995). Figure 1 represents the model for evaluating a science program.

As it is seen in Figure 1, program evaluation in science consists of three general phases, such as a contextual evaluation of the program’s overall framework with its goals and objectives, evaluation of the implementation process, and evaluation of the program’s output. For creating a base in program accountability, the evaluation attempts should be (1) comprehensive in collecting information from all the related elements and stakeholders, (2) combinations of different program evaluation approaches, and (3) using both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis procedures.

For ensuring comprehensiveness of the information collected, program accountability should also rely upon judgmental evaluation of experts, teachers, school administrators, education policymakers, stakeholders, and customers, besides student-related learning outcomes (Gredler, 1996; Morris et al., 1987; Posner, 1995; Stecher and Davis, 1987; Worthen et al., 1997).

Even though evaluation approaches vary in terms of research methodologies, criteria to be focused on, nature of the data collected, and standards to be addressed for quality indicators, all the approaches try to collect as much evidence as possible to prove that the program under investigation operates as intended (Herman et al., 1987). Thus, a unified approach with the combination of various evaluation methods would provide a wider range of information with regard to the quality of a science program.

The use of both quantitative and qualitative approaches should be favored since any important finding in quantitative analyses could be probed via qualitative techniques.

On the other hand, as seen in Figure 1, the successful implementation of a science program also relates to student and teacher background characteristics, as well as the infrastructure of the school, as intervening variables.

Evaluation is a decision-making process through which a judgmental conclusion is drawn, based on information collected at different phases of the program-evaluation model, as depicted in Figure 1. The most critical issue in this process is selecting appropriate criteria to decide about the quality of the program. When the steps of the science evaluation model is considered, coverage of the standards defined in the conceptual framework of the program – with respect to basic skills and knowledge universally accepted in science education, valid and congruent implementation of instructional modes, materials, laboratories, etc., in the classroom – and attainment of skills and attitudes by students, could be the major focus of the evaluation process.

- 1. A program evaluator should consider the following for each phase of the program evaluation:

2. Determining the tasks to be evaluated.

3. Planning the process to collect information about the tasks.

4. Determining criterion against which the quality will be addressed.

5.Integrating all the information collected.

6. Judgmental decision with regard to the overall success of the program.

The following sections provide examples for the tasks to be evaluated as well as criteria to be considered in each step of the evaluation model given in Figure 1.

Contextual evaluation

This phase, basically, focuses on the definition of the program. Successful implementation of the program requires a well-defined overall goal, instructional objectives, and planned activities. There are always differences between the program’s overall planned structure and what is being implemented in practice (Marsh and Willis, 2007). Thus, before evaluating the program implementation and outcomes, the contextual evaluation of a science program constitutes a base for the program implementation.

In the definition of a science program, there should be at least two dimensions to consider: subject matter and cognitive processes.

The selection of appropriate subject matter and their sequence and organization are the primary tasks to be considered at this very first stage. Selection of subject matter is a function of age and grade levels, but it is linked to cognitive processes as well. In general, subject matter in science consists of facts, concepts, and principles. For meaningful learning to take place, the subject matter should be in congruence with the developmental level of the students. Any concept which is too abstract for the learners will hinder meaningful learning. This issue is rather the validity of the subject matter domain and its significance with reference to the needs of the students and society (Oliva, 2001). A program evaluator should take the developmental stages of the students into consideration as well as the needs of the stakeholders in assessing the appropriateness and sequential organization of the subject matter.

Cognitive processes, on the other hand, are the higher-order thinking processes which are inquiry skills in science that are required through all the age and grade levels. After clarifying the overall goal of a science program, the primary concern of the program developer is to link the cognitive processes with the subject matter, through the program’s objectives, as learning outcomes.

For an evaluator, the major questions to ask at this phase are: How well was the program planned and designed in line with the subject matter and cognitive process? Were the objectives correctly selected and defined? In a science program, the objectives could be planned and designed with respect to various approaches, such as behaviorist or cognitive (Klopfer, 1971; Marzano et al., 1988; Royer et al., 1993). With the increasing impact of constructivism on program-development attempts, science programs could be designed in spiral curriculum format – through which the same cognitive skills can be repeatedly introduced to students through all the grade levels (Henson, 2006). Since the evaluation of this domain constitutes the appropriateness of the program’s overall structure, no matter which approach is being used, the primary concern should be the content of the cognitive processes program covers. No matter which program-development approach is used, besides basic conceptual understanding, the science program should emphasize inquiry skills in stating its objectives.

| Process skills | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Transfer | Converting one form of information into another. |

| Prediction | Based on a criterion anticipating a future condition. |

| Relating | Link at least two body of information with each other. |

| Providing examples | With reference to a given situation proposing a novel example. |

| Classification | With reference to at least two groups of information, locating or naming a given case. |

| Hypothesizing | Based on an observation result proposing a statement which is testable. |

| Observing | Based on five common senses describing attributions or properties of a given event or object. |

| Conducting experiments | Based on a hypothesis, designing an experimental apparatus. |

| Data collection | Collecting or analyzing data with reference to a given hypothesis. |

| Drawing conclusion | Providing a statement that may support an experimental hypothesis or observations. |

Science Education

The evolution of formal school science education, in response to changing attitudes toward science, is summarized. The content and structure of the curriculum, including the relationships to technological applications and to the nature of science, are presented. Assumptions about learning, assessment, and science teacher education are given. The evolution, the nature and provision, of informal science education is summarized. The nature and use of research into both formal and informal science education are briefly discussed.

The Rise of STEM Education

The Framework for K-12 Science Education (Framework; NRC, 2012) presents a new vision of science teaching and learning in which students are to develop knowledge to make sense of phenomena or design solutions to engineering problems. Because of the uniqueness of what the Framework and the resulting Next Generations of Science Standards (NGSS; NGSS Lead States, 2013) proposed, districts are currently grappling with finding ways to address the NGSS at the elementary level. In this paper, we present one promising solution.

One of the most significant–and challenging–innovations put forth in the Framework and NGSS is a call for “three-dimensional science learning.” Three-dimensional science learning means that students use science and engineering practices, core scientific ideas, and crosscutting concepts that span science disciplines together in an integrated manner to explain phenomena or solve problems. For example, to figure out why some bird species prefer wetlands over prairies, a student would need to use science and engineering practices like carrying out an investigation and analyzing data of a bird’s habitat, while thinking about the phenomenon through the lens of crosscutting concepts like systems and cause and effect, and also applying core ideas about ecology such as interdependent relationships.

Project-based learning (PBL) is a curriculum approach that shows promise in creating environments for meaningful student learning, including three-dimensional science learning (Miller and Krajcik, 2019; Miller et al., 2021b). Researchers describe PBL in different ways, but they always include the following features: (1) An artifact that drives and culminates a cycle of investigation, (2) Driving Questions that motivate practices and are answered by the artifact, and (3) Student learning has authentic and student-centered application (Barron et al., 1998; Krajcik and Blumenfeld, 2006).

As part of a large design-based research project, our team designed upper elementary project-based learning environments that extended our vision of PBL to three-dimensional learning. Our task was to develop and refine units of instruction that would provide evidence of the value of PBL in promoting three-dimensional science learning and community. This paper reports on the design cycles that led to our final third and fourth grade products, prior to an efficacy study and the testing of fifth grade materials.